Bicycle Boulevards - are they good?

They appear to be a simple street with some paint - should they be considered good cycling infrastructure?

A bike boulevard at its core is a street, often with car parking, no dedicated bike lane, a painted bike, and text indicating its purpose. Most would not consider this to be cycling infrastructure, given that there is no visible protection in place to separate bikes from cars. There’s a risk of getting doored or a car passing a bit too close for comfort. But from a planner’s perspective, a bike boulevard shouldn’t be on busy roads where that is likely to happen. They tend to be quiet streets, often in neighborhoods, one or two blocks off a main thoroughfare. So, the infrastructure needed to separate cars from bikes could be minimal.

However, bike boulevards are often seen as the cheapest way to implement "bicycle infrastructure" because all that is needed is some stencils and white paint. If a city is trying, they'll even add street signs with directionals for other cycling routes. What can happen when cities get this wrong, is a) a broken network of cycling infrastructure and b) an unsafe street that cyclists don't feel safe riding on.

What Makes a Great Bicycle Boulevard

NACTO's Take on Bicycle Boulevards

From their Urban Bikeway Design Guide, NACTO (National Association of City Transport Officials) outlines eight key tenets of the bicycle boulevard:

Route Planning: Direct access to destinations

Signs and Pavement Markings: Easy to find and to follow

Speed Management: Slow motor vehicle speeds

Volume Management: Low or reduced motor vehicle volumes

Minor Street Crossings: Minimal bicyclist delay

Major Street Crossings: Safe and convenient crossings

Offset Crossings: Clear and safe navigation

Green Infrastructure: Enhancing environments

Placing bicycle boulevards between origins and destinations is key, the key to all transport infrastructure, in fact. But bicycle boulevards aren't the best solution for providing direct access to all destinations, especially those that are car-oriented, on busy streets with street or off-street parking for cars. Those destinations would be better served with a protected bike path as opposed to a bicycle boulevard in most cases. But a boulevard can be a great connector in the overall network.

One of the great killers of a bicycle boulevard is the high car volume. At its core, a street picked to be a bicycle boulevard should be a quiet street that is not a major arterial or collector road. That's why it's thought to be acceptable to mix cars and bikes because, at these lower volumes and speeds, cars have greater time and space to move around cyclists or find an alternative route that better suits them.

Another consideration for bicycle boulevard safety is crossing intersections. With the prevalence of street parking and the growing personal vehicle size, it can be difficult to judge whether or not a car is approaching the intersection. Often, riders can't see over the parked cars and can only see the vehicle approaching once they are vulnerable in the intersection. Now, this should be less of an issue if the bikeway is given priority (i.e., a two-way stop for crossing streets). However, cars don't always stop at intersections. So, knowing where the cars are is only half the battle, but having that knowledge will allow the rider to navigate smarter.

Some ways to combat unsafe intersections through infrastructure are known as traffic calming measures (read: anything that will slow cars down). Some common traffic calming tactics are to place concrete/green medians at intersections. Some of these prevent vehicle crossings but allow cyclists through. Some also allow a resting place for pedestrians crossing the street, making it safer for them. Another common tactic is narrowing the road just before the intersection. In the early stages of road reconstruction, this is often seen in the form of plastic bollards that remove street parking near the intersections and shorten the distance between the two sides of the street. Later, these intersections are converted to grass bump-outs with accessible sidewalk crossings, as seen below.

The Great, The Good, and The Ugly

Let’s look at some real-world examples of bicycle boulevards to see how they can be done well and how they can come off half-baked.

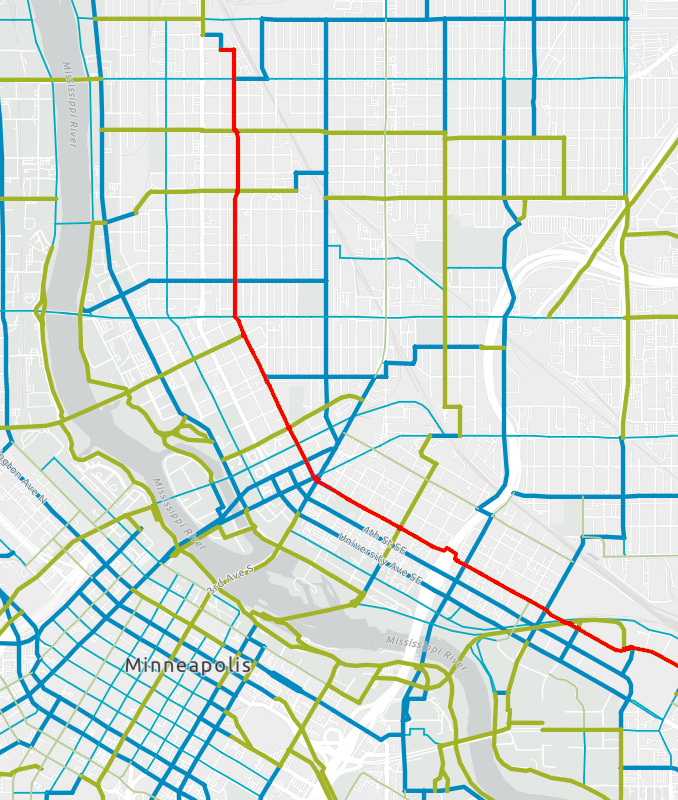

A Great Bike Boulevard - 5th St NE & SE, (Minneapolis, MN)

5th Street NE is a bike boulevard that provides cyclists a quiet street to ride and get a fair distance on each side of Broadway St NE. What makes it work is that it is blocked off from car traffic on the south side of Broadway. This prevents through traffic (cars specifically) and keeps all traffic local and minimal. It's a great way to get from Hai Hai to the University of Minnesota, for example, and it even gets its own pedestrian/cycling-only bridge over I-35W.

Some improvements could be made through the Nicolet Island neighborhood (not the island) to make it easier for cyclists to cross 1st Ave NE, Hennepin, and Central. Currently, it does not feel safe to cross these wide roads (although 1st and Hennepin are one-way), but improvements are coming, so that may change in the coming year.

South of Hennepin, 5th St becomes a one-way for cars but dedicates a small lane for cyclists going in the opposite direction. This is great and still offers street parking on one side. The downside to 5th St SE is the lack of traffic calming. The onesided street parking improves sightlines a bit, but some cross streets still are blindspots for cyclists.

Overall, 5th St offers some great bike boulevard features such as clear markings, destinations, and (some) traffic calming measures. Where it could improve is where all Minneapolis streets could improve, and that's sightlines at intersections. Four-way stops can help but are often not enough to stop cars from rolling (or blasting) through intersections.

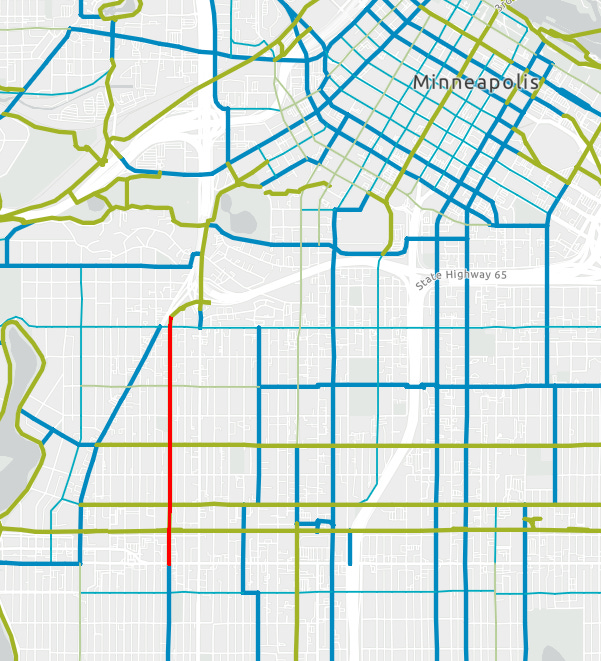

A Good Bike Boulevard - Bryant Ave S, North of Lake (Minneapolis, MN)

Byrant Ave S is a decent bike boulevard that connects the Loring Greenway to the Midtown Greenway and the Uptown neighborhood. It's a two-way street with parking on both sides, so it doesn't quite have the width for all the traffic it needs to support. It does not connect directly to Hennepin, making it fairly quiet and local. It has traffic calming in the form of speed humps but does not have any calming measures for intersections, most of which are two-way stops giving the one-way crossing roads priority. At least the sightlines here were decent, so sitting and waiting for a gap didn't leave you super exposed.

Improvements could be made to the intersections, especially since crossing traffic sometimes feels as though the cars are at highway speeds, especially on the one-ways. The road can't be widened (and shouldn’t be), so making more space for traffic can only really be achieved by removing parking on one side, which limits growth on this street. (Not saying it needs to grow, just that it can't without sacrifice).

Overall, it is a short but vital part of the network that connects two major greenways and the local neighborhoods, providing a good way to get around by bicycle. Given the density in this area and the importance of this connection, I'd like to see this part of Bryant Ave upgraded to something beyond a bicycle boulevard. South of Lake Street, Bryant Ave has been overhauled into a one-way street with a dedicated, elevated two-way cycle path. This could easily be copied on the section north of Lake Street (in red on the map) to make a safer cycle path to connect the two greenways.

A bad Bike Boulevard - E 23rd Ave (Denver, CO)

Looking at Denver's Bike Map from 2023, 23rd Ave, west of City Park, is not yet listed as a "neighborhood bikeway", which is their name for a bicycle boulevard, so this could be a WIP route. As it stands now, it is paralleling two similar bikeways - E 22nd Ave and E 25th Ave.

23rd Ave serves as a collector road through the City Park and should not be supporting local bike traffic as it is today. Given the vehicle volumes that the street serves, bicycles should be separated from cars. There are also surprisingly few connections to the destinations west of the park. The grid changes its orientation and forces cyclists north to the 26th St bikeway or south into neighborhood streets and collectors.

Comparing this road to NACTO's criteria, it fails on a few fronts, most notably the volume of traffic. There is also little signage to indicate that this is a bicycle boulevard other than the paint on the street surface itself. It doesn't show other bikeways or routes that it connects - it doesn't connect to much of anything. There is also zero traffic calming. The only parking restrictions are indicated by signs, not by bollards or bump-outs, so judging the crossing traffic is difficult.

As a visitor to this area, I don't feel fully qualified to judge its effectiveness for the community, but I can say it felt odd seeing this bicycle boulevard here, if only for a short distance. It doesn't feel like part of a greater network of cycling infrastructure, just a stub that goes nowhere. That said, I'd love to go back and explore more of the cycling infrastructure in Denver as I felt there was a decent number of cyclists, just not great infrastructure to serve them.

Verdict

The bicycle boulevard is simple on the surface but needs thought and proper planning to implement and integrate it into an overall bicycle network. I don't think they should be overlooked as a viable means of infrastructure. They can offer a great route through relatively dense areas by routing bikes through the quieter streets, rather than main thoroughfares. But getting them wrong does have consequences for cyclists who aren’t able to be safely connected to their surrounding communities.